Minimal Docker containers with Go using GitLab CI

Contents

General

I’ve been fascinated with minimalism with Docker and containers for a long time. That has lead me to exploring scratch-containers and statically linked executables. As I don’t have that much experience with c or c++ and wanted to try something new anyway, I picked up some go and started figuring out what would be the easiest way to achieve statically linked, minified images.

While figuring out what’s the best way to build a Docker image out of the executable I ran into go-lang-builder by CenturyLinkLabs. They provide a really easy way to build the executable using a container to build a container which makes it trivial to do the build as part of a CI/CD process.

The example program

I wrote a small program that returns an image with varying colours based on the host name (of the container) that it’s running on. This can be used to demonstrate scaling and the effect of load-balancing in a distributed environment.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

/*

A simple test program that returns a yin/yang image with varying colour

depending on a hash calculated from the hostname. Useful for demonstrating

scaling in for example a container based runtime environment.

*/

package main // import "gitlab.com/sirile/go-image-test"

import (

"fmt"

"log"

"net/http"

"os"

)

var colour string

var hostname string

func main() {

// Get the hostname and calculate a hash based on it

name, err := os.Hostname()

hostname = name

hash := 0

for i := 0; i < len(name); i++ {

hash = int(name[i]) + ((hash << 5) - hash)

}

// Generate a colour based on the hostname hash

colour = "#"

for i := uint(0); i < 3; i++ {

hex := "00" + fmt.Sprintf("%x", ((hash>>i*8)&0xFF))

colour += hex[len(hex)-2:]

}

if err == nil {

log.Printf("Serving image, host: %s, colour: %s", hostname, colour)

http.HandleFunc("/favicon.ico", func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {})

http.HandleFunc("/", handler)

http.ListenAndServe(":80", nil)

}

}

// Serve the content

func handler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

fmt.Fprintf(w, "<!DOCTYPE html><html><head>"+

"<title>Go scaling demo</title></head><body>"+

"<h1>%s</h1>"+

"<svg xmlns=\"http://www.w3.org/2000/svg\" viewBox=\"0 0 400 400\">"+

"<circle cx=\"50\" cy=\"50\" r=\"48\" fill=\"%s\" stroke=\"#000\"/>"+

"<path d=\"M50,2a48,48 0 1 1 0,96a24 24 0 1 1 0-48a24 24 0 1 0 0-48\" fill=\"#000\"/>"+

"<circle cx=\"50\" cy=\"26\" r=\"6\" fill=\"#000\"/>"+

"<circle cx=\"50\" cy=\"74\" r=\"6\" fill=\"#FFF\"/>"+

"</svg>"+

"</body></html>", hostname, colour)

log.Printf("Served image, host: %s, colour: %s", hostname, colour)

}

The program itself is naive, but I wanted to see the difference of the image size compared to nodejs and Java versions of the same program, i.e. how much the runtime environment adds.

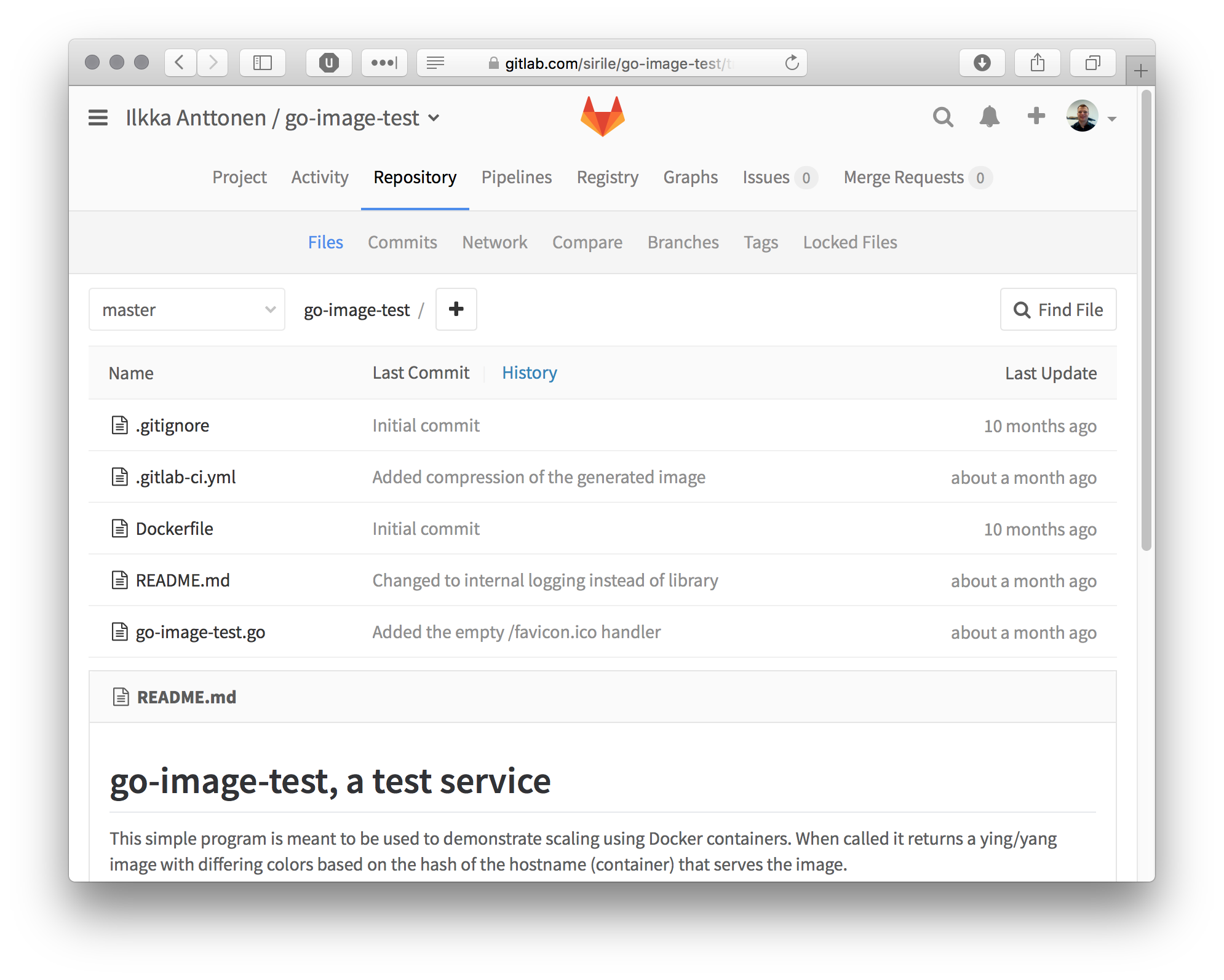

All the code is available at GitLab

repository which looks like

Building and running locally

Provided you have the go-development environment set, the program can be compiled

with go build <filename.go>. When you run the program it wants to use the port

80, so you may need to use sudo for it to get access to that port. Then it

can be tested with hitting it with browser.

Building with go-lang-builder

Base dockerfile

Go-lang-builder expects a Dockerfile to be present in the directory. In this example it looks like

1

2

3

4

FROM scratch

EXPOSE 80

COPY go-image-test /

ENTRYPOINT ["/go-image-test"]

Creating the image

If you are using Docker for Mac or Docker for Windows (or just DockerToolBox) and have the environment set up so that the docker client points to a Docker engine, building an image is done with

1

docker run --rm -v "$(pwd):/src" -v /var/run/docker.sock:/var/run/docker.sock centurylink/golang-builder

This expects the project directory structure to match what is described at the go-lang-builder documentation.

If you want to minimize and tag the image straight after build, the command is

1

docker run --rm -v "$(pwd):/src" -v /var/run/docker.sock:/var/run/docker.sock -e COMPRESS_BINARY=true centurylink/golang-builder go-image-test

Running locally

The created and tagged container can be started with

1

docker run --rm -p 80:80 go-image-test

and it should be available at port 80 of the Docker node.

Building on GitLab using GitLab CI

GitLab offers a nice CI which works well with the idea of using build container to build the actual image. They also offer a repository which can be used to host the created image file. The system works with a configuration file being in the project root. It offers a lot of possibilities, but in this test I just wanted to build and push an image in case the go-source code is modified.

Buildfile (.gitlab-ci.yml)

After some trial and error the buildfile looks like

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

image: gitlab/dind

variables:

CONTAINER_TEST_IMAGE: registry.gitlab.com/sirile/go-image-test:$CI_BUILD_REF_NAME

CONTAINER_RELEASE_IMAGE: registry.gitlab.com/sirile/go-image-test:latest

before_script:

- docker login -u gitlab-ci-token -p $CI_BUILD_TOKEN registry.gitlab.com

build:

stage: build

script:

- docker run --rm -v "$(pwd):/src" -v /var/run/docker.sock:/var/run/docker.sock -e COMPRESS_BINARY=true centurylink/golang-builder $CONTAINER_TEST_IMAGE

- docker push $CONTAINER_TEST_IMAGE

First there’s a log in to the registry offered by GitLab by using the credential system they provide (so that there’s no need to hardcode the credentials). Then the build container is run and when the image is built it is pushed from the temprorary build-machine registry to the GitLab user registry.

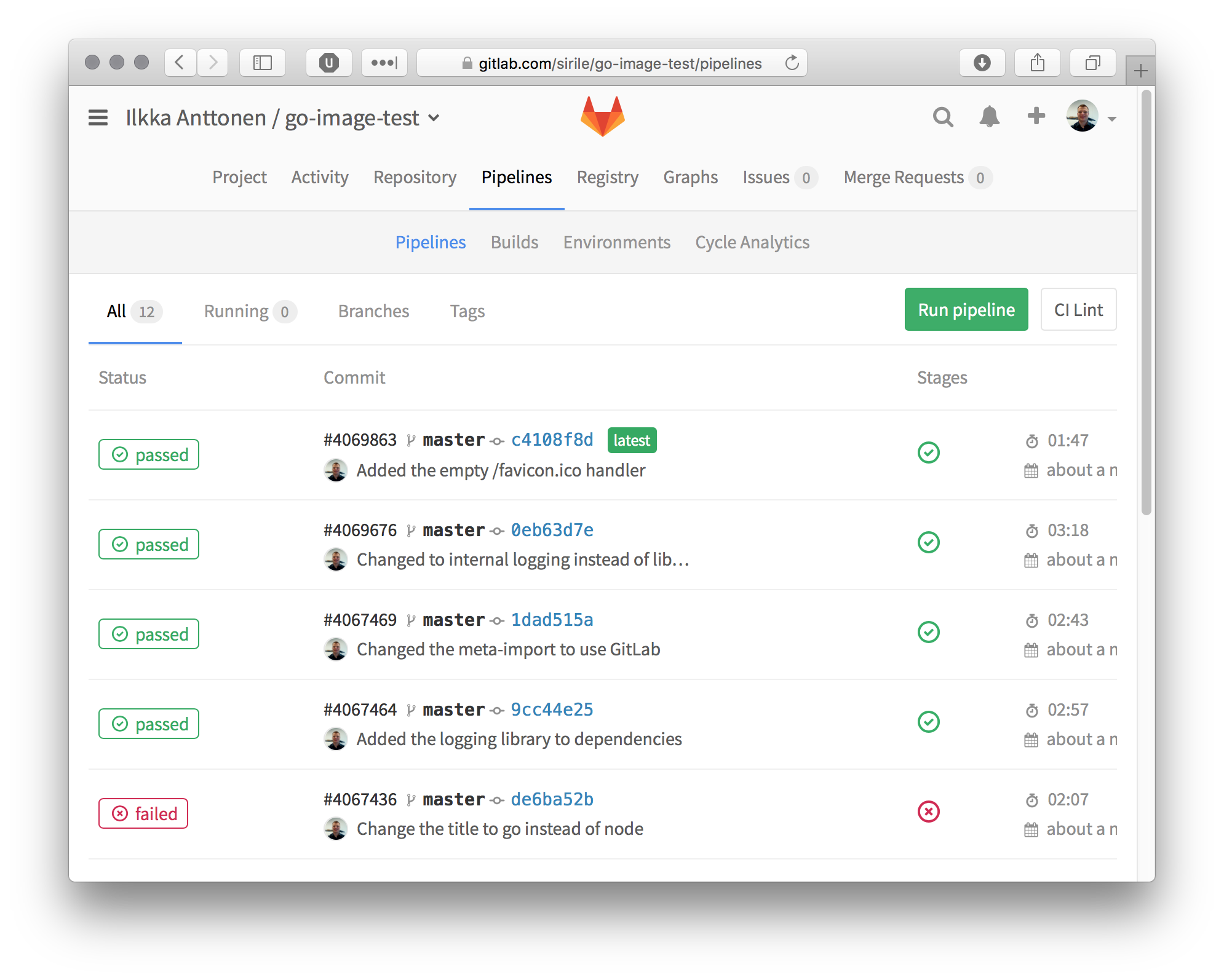

If the build fails, the logs are retained and can be browsed from the build

pipeline view, which looks like

There should (of course) be tests that verify that the image actually works before pushing it onwards. After doing the release, the system could notify the orchestration provider used to provide the production runtime environment that a new version of an image is available and then the orchestration system could for example do a staged deployment, check that things work and retire the old version.

Results

The other test images I had use minimal Alpine-based base images. The scala-boot-test is a bit more complex as it uses Spring Boot and Scala, which adds about 30 MB to the image size with the needed libraries.

1

2

3

4

5

$ docker images

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

registry.gitlab.com/sirile/go-image-test master 5b0dc09ada6d 4 weeks ago 1.616 MB

sirile/node-image-test latest fac8464c4ad6 3 months ago 47.28 MB

sirile/scala-boot-test latest c778530c2a88 5 months ago 191.4 MB

The difference in the container sizes is considerable. If the go-based

executable is left uncompressed by omitting the -e COMPRESS_BINARY=true-flag,

it’s about 5.6 MB. I haven’t run tests comparing the execution speeds of

compressed or uncompressed binaries.

Conclusions

When striving towards minimalism the idea of statically linked executables works. Then the scratch-container can be used which results in the absolutely smallest possible containers. To get containers smaller, the language would need to be switched to c or assembler, but go has good traction and I would deem the results as small enough.

Positives

As there is no file system or any other running processes, the container can be made read-only if wanted. The attack surface is practically non-existent and the worst that can happen is that the executable terminates (which may lead to a restart loop if the container orchestration is so configured). The only way to hack something like this would be through kernel exploits as far as I understand the Docker security model, as there is no shell to gain access to by crashing the executable.

Drawbacks

As the scratch container doesn’t include a file system, it also doesn’t have

any command line tools like a shell which could be useful when debugging. If

the executed program is such that would benefit from it, I suggest that Alpine

based base-image would be used instead, which enables the use of docker exec

and similar methods to gain access into the executing container. This may of

course add an attack vector.

Comments